The rapid advance of M23 — supported by the Rwandan military (RDF) — in North Kivu has taken most of us by surprise over the past week. By the morning of January 29th, the rebels largely controlled the strategic city of Goma, except for some last pockets of resistance by Congolese army soldiers and allied armed groups. On February 3rd, the UN reported that at least 900 people were killed in the siege of Goma, and highlighted incidents of summary executions, as well as cases of sexual and gender-based violence, and the destruction of displaced persons camps. The latest crisis also displaced another 237,000 people since the start of 2025 — while the Kivu provinces were already home to 4.6 million internally displaced people at the end of last year. Additionally, the UN warned for a looming health crisis, citing the risk of massive spread of mpox, cholera and measles due to further displacement and the lack of medical care. The security and humanitarian risks are further exacerbated as M23 is continuing its offensive in the direction of Bukavu, in South Kivu.

To provide a quick and understandable explanation of the causes of this humanitarian crisis, the role of natural resources, and in particular minerals, is often overemphasized. While mining and mineral trade inevitably play an important role — being a vital part of the local economy — it is important to assess economic assets more broadly, as well as political interests and social grievances.

A wider range of conflict drivers have come together in the latest upswing of violence. Many different actors are involved, each with their own agenda. On top of that, several events and political decisions have added fuel to the fire over the past two years. This led to the current escalation of violence in eastern DRC. Below, we have prepared a Q&A that attempts to answer the most important questions concisely, while highlighting the various aspects and complexities.

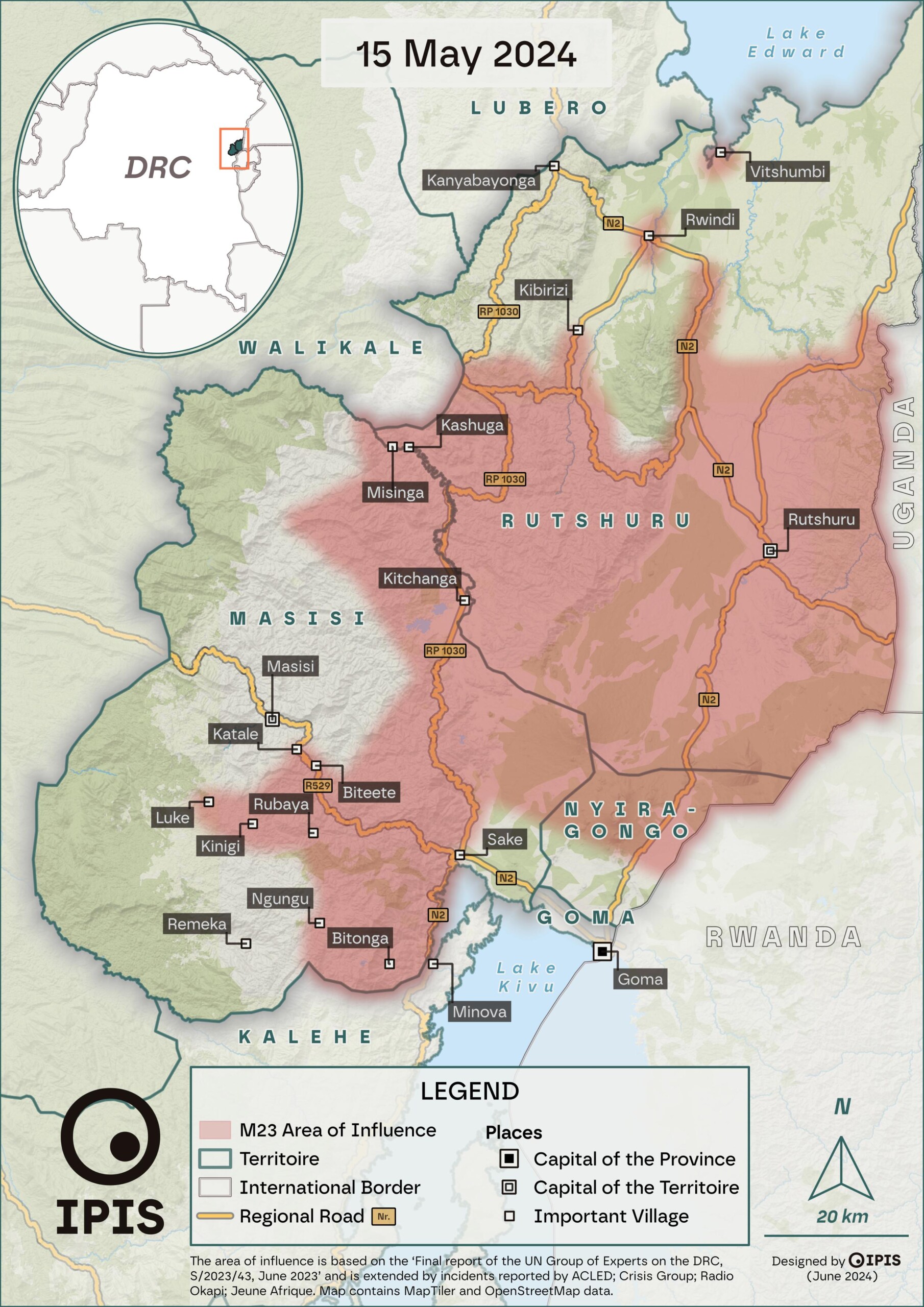

What does M23’s territorial expansion look like?

Map 1: Area influenced by M23, January 2025.

M23’s occupation of (parts of) North Kivu is not new. It has continuously made significant territorial gains in North Kivu since the end of 2021, and established parallel administrations in the areas it has conquered. Map 1 shows M23’s area of influence, covering the territories of Rutshuru, Nyiragongo, and (most of) Masisi. Late January 2025, M23’s area of influence covered about 7,800 km2.

Until late January 2025, however, international attention for eastern DRC was limited as M23 did not venture into Goma, the main city in eastern DRC, although it had already encircled the city for almost a year. M23’s capture of Goma in 2012 created a lot of international and diplomatic indignation, which marked the end of its insurgency at the time. It was therefore believed that M23 would not make the same mistake again. But then, late December 2024 M23 launched a new offensive. On January 21st it captured Minova in Kalehe territory (South Kivu), and Sake — the last stronghold before Goma — fell around January 24th. (See inset map 1.)

Additionally, since December 2024, M23 also made some attacks on its northern front near Bingi, in Lubero territory. And its currently heading further south into South Kivu province, where it reportedly captured Nyabibwe on February 5th.

Why is M23 fighting?

While Rwandan army support is a crucial factor in explaining M23’s resurgence back in 2021, the movement is not merely a proxy of Rwanda. It first and foremost pursues its own interests and objectives.

M23 was first created in 2012 by former officers of the Congrès National pour la Défense du Peuple (CNDP) who were dissatisfied with the government’s implementation of a 2009 peace agreement, that should have allowed CDNP to transform into a political party and its military units to integrate into the FARDC. In 2021, M23 resumed fighting after the failure of confidential negotiations between the Congolese government and M23 concerning the implementation of the 2013 Nairobi Declarations, which had ended the first M23 rebellion.

M23 believes that the government is not adequately securing the Rwandaphone communities in eastern DRC, including protecting them from hate and armed groups. The tensions between these Rwandophone communities (Hutus, and especially Tutsis) and North Kivu’s other ethnic groups date all the way back to the colonial and post-independence periods. Competition over access to land, and the role that local authorities play in land management, have fed tensions that pitted communities against each other. Over the past decades, the Congolese government never managed to ease these tensions nor to guarantee people’s land property rights. Initially, the goal of M23 was to eradicate rival armed groups, to secure land control by overtaking local power — and in particular to protect land acquired by the “Tutsi” community — and to integrate into the national army.

What is new, however, is that M23’s demands have increasingly taken on a national political dimension, going beyond the protection of Rwandophone communities in the Kivu provinces. The movement is now also turning directly against the regime in Kinshasa. This is further emphasized by its pact with the Alliance Fleuve Congo (AFC), which is seen as M23’s political wing. AFC was founded in December 2023 by the former chief of the electoral commission Corneille Nangaa, who stated “Our objective is neither Goma nor Bukavu but Kinshasa, the source of all the problems”. President Tshisekedi has always perceived the AFC as an effort from former president Kabila to oust him, saying “the AFC is him”.

Whether M23 actually wants to overthrow the current government remains to be seen. At present, its primary objective appears to be pressuring Kinshasa into direct negotiations, with the aim to integrate its units into the national army, to secure important positions within the army, and potentially even participate in the Congolese government.

How did the Congolese government deal with M23’s resurgence?

Félix Tshisekedi assumed power in 2019 after disputed elections, which many believe involved a corrupt agreement with the outgoing President Joseph Kabila. During his first term, President Tshisekedi was preoccupied with building and reforming his (shaky) presidential coalition, and his policy achievements were quite weak. While it must be said that the security situation in the East that he inherited was already bad, his policies have only made the situation worse.

In 2019, Tshisekedi stepped up regional diplomacy to establish political and security cooperation with neighboring countries. While regional diplomacy and cooperation is important, this strategy seemed to underestimate — and even exacerbate — historical tensions between different regional leaders who have historically fought for influence in eastern DRC. Moreover, these regional alliances — especially the one with Rwanda — have been met with deep suspicion within the DRC, and fueled a resurgence of anti-Rwandan and anti-Tutsi sentiment. (Many Congolese still view Rwanda and its military as an adversary due to its role in the Second Congo War.) Secondly, the government declared a state of siege in May 2021 to cope with escalating violence in Ituri and North Kivu, but the security situation drastically deteriorated and the measure worsened the human rights situation in the country. Third, because the Congolese army (FARDC) is unable to stop M23’s expansion — due to structural issues like chain of command problems, corruption, unsuccessful reforms, failed integration processes of armed groups and demotivated troops — the army and the government chose to fight the group by proxy. They provided covert military and financial support to a coalition of Congolese armed groups (later on branded as “Wazalendo”, or patriots in Kiswahali), including Kigali’s sworn enemies of the Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR). Critically, renewed recruitment and rearmament by these armed groups undermines past and future Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) initiatives. Fourth, Kinshasa has pursued a narrow military strategy against M23 over the past years, refusing to negotiate with them as it considers them as a terrorist group. Whether or not this decision is justified, it has ignored the military reality on the ground. Every time the Congolese army or its allies have launched an offensive, this backfired and led to renewed M23 expansion. Finally, Tshisekedi was rather volatile in the military alliances he made. He urged the MONUSCO to withdraw from his country, and Blue Helmets already left South Kivu in June 2024. In the course of 2024, however, the government appeared to reconsider this, at least for the time being, as the security situation further deteriorated in North Kivu. He has also invited multiple private security firms, international forces (EAC and SADC), and national armies (e.g. Burundian), only to dismiss some of them soon after. This inconsistency fuels the chaos and risks exacerbating regional tensions.

What is the link with national politics?

While Tshisekedi was re-elected at the end of 2023, the opposition questioned the validity of electoral results due to massive logistical problems. Additionally, political opponents now fear that Tshisekedi will seek another term by changing the constitution, which would allow him to stay in office beyond 2028. These actions have prompted some key political opponents to take a stand, with former President Joseph Kabila and Moïse Katumbi working toward a united political alliance against Tshisekedi.

As the M23 crisis continues to escalate, the question arises as to whether this could also mean the end of Tshisekedi’s government. The political opposition in Kinshasa first and foremost condemns Rwanda for its support of M23. But many are also holding Tshisekedi accountable and are criticizing his approach to the security situation in eastern DRC. Nevertheless, Katumbi and Kabila are being watched with suspicion by the government, as they have so far failed to comment on the latest developments in the Kivus.

Ever since President Tshisekedi outmaneuvered Kabila and removed him from the political majority in 2020, he has considered him a threat. He is also convinced that Kabila is behind the creation of the Alliance Fleuve Congo (AFC) and its links with the M23 rebellion. Despite mistrust of M23 — due to its backing from Rwanda — support for AFC might actually grow as political opposition against Tshisekedi increases.

Whatever Kabila’s influence over the AFC may be, the fall of Goma — the capital of North Kivu and the main city in the east — and the M23’s decision to march on Bukavu further weakens Tshisekedi’s credibility, and thus undermines his political future.

Did Rwanda get involved?

M23 would never have managed to realize such an impressive territorial expansion without the support from Rwanda. The UN Group of Experts documented in several reports how the Rwandan army is providing military equipment and training for M23. They even reported the presence of 3,000 to 4,000 Rwandan soldiers in North Kivu, fighting alongside M23, which was only a conservative estimate according to some observers. The DRC Foreign Minister Thérèse Kayikwamba Wagner reported that additional Rwandan troops had crossed the border in the run-up to the siege of Goma, and some reports now mention there may be up to 5,000 Rwandan soldiers in the province. The UN Group of Experts also reported that operations in North Kivu are being coordinated by President Kagame’s adviser, General James Kabarebe. The latter was already involved in M23’s chain of command in 2012, when he was Minister of Defense in Rwanda.

Why did Rwanda get involved?

The reasons for Rwanda’s support to M23, and its interference in North Kivu more generally, are very complex, including security concerns, as well as regional political and economic competition for influence in eastern DRC and the wider region.

Ever since the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, Kigali has insisted on the security threat posed to Rwanda by the situation in eastern DRC. The dismantling of the FDLR (an armed group created in 2000 by former perpetrators of the genocide) is a security priority for them. Some observers, however, see Kigali’s security concerns as a pretext to continue asserting influence over eastern DRC. FDLR is still an important armed group in the south of North Kivu with an estimated 1,000 to 1,500 combatants, but they reportedly no longer pose an imminent threat to Rwanda. However, Rwanda’s support for M23 is also a self-fulfilling prophecy, in the sense that it revives FDLR’s collaboration with the Congolese army and enables them to ramp up recruitment efforts.

Nevertheless, regardless of the threat the FDLR might or might not pose to Kigali, it does not take away the fact that the genocide is a traumatic experience, and thus the fear of violence may well be an important sentiment in Rwanda. Yet again, Jason Stearns also explains very well how Kagame’s RPF needs the outside security threat to legitimize their regime and to suppress opposition and dissident voices: “Given the central place the genocide still plays in Rwandan memory and politics, the FDLR remains a powerful symbolic threat.”

Second, eastern DRC provides important economic opportunities for its neighboring countries, including Uganda and Rwanda: they compete to profit from the export of DRC’s natural resources, but also the sales market that DRC offers for agricultural products, consumer goods, and services. In 2021, just before the resurgence of M23, the (fragile) regional balance of power in the Great Lakes region was upset. Kigali perceived a threat to its ‘zone of influence’ in the DRC: Uganda and the DRC had announced a security collaboration and road rehabilitation project in the DRC, while at the same time, earlier promises of increased gold trade from the DRC to Rwanda (e.g. an agreement with the Rwandan gold refiner Dither), as well as military collaboration, were suspended.

The rift between the current Congolese regime and Kigali also seems to have become irreconcilable, since Tshisekedi ramped up nationalist rhetoric against Rwanda as part of his electoral campaign in 2023. The government engaged a law firm to denounce the smuggling of minerals to Rwanda, and called for a boycott against the latter’s 3T (tin, tungsten, tantalum) mineral exports.

Nevertheless, it seems Kagame feels more empowered than ever to dare another attack on Goma by M23. While Europe has condemned Rwanda’s support to M23, Kigali knows that Europe increasingly needs Rwanda as a ‘stable’ partner on the African continent in the fight against terrorism, and in the geopolitical struggle for fossil and mineral resources. This includes, for instance, the signing of a MoU on Sustainable Raw Materials Value Chains and a military aid package for Kigali linked to the deployment of its troops in Mozambique.

This collaboration with Kigali is not well received in DRC. Congolese politician Christophe Lutundula referred to Rwanda’s intentions, and Kagame in particular as follows: “He wants to demonstrate to the international community that he is the only valid interlocutor with whom to deal on issues of security, peace and even cooperation with the Great Lakes region. … If you want to deal with the Great Lakes region, it is me you will have to deal with.”

Kigali’s immediate objective behind the latest M23 offensive is fodder for speculation. In any case, it seems M23’s siege of Goma has been triggered by the failed negotiations in Luanda in December 2024, when the DRC categorically rejected Rwanda’s demand for a direct dialogue between M23 and the DRC. M23’s territorial expansion and capture of important cities would increase pressure on Tshisekedi to agree to direct negotiations with M23, which further undermines Tshisekedi’s position and increases Rwanda’s influence in the east. As such, the fear of “balkanization” — which is the widely held belief in DRC that the international community, and Rwanda in particular, are trying to divide the DRC — looms around the corner. Some sources believe that Kigali may be looking for a more permanent M23 occupation of the Kivus, with a Kigali-friendly administration, or even regime change in Kinshasa altogether. This feeds into the analysis of some observers that Rwanda intends to create a buffer zone in eastern DRC, which would serve both the strategic economic and security concerns mentioned above.

What about minerals?

Minerals do play a role in conflict financing in eastern DRC and are part of the broader regional geopolitical tensions. This is logical, given that mining and mineral trade are an important part of the local economy and regional trade flows. Still, minerals should not be considered as the primary cause of conflict. In reality, conflicts in eastern DRC are much more complex, turning around contested authority, disputed access to land and resources, unresolved issues of national citizenship, historically unaddressed social inequalities, and struggles for political power.

Over the past decades, numerous armed groups have mushroomed in eastern DRC, claiming to protect the interests of various local communities and relying on minerals, among other sources of income, for their survival. Over time, many of these groups increasingly shifted toward rent-seeking behavior.

For M23, a similar trend emerges. Initially, the movement sought to safeguard the interests of the Tutsi community, particularly by ensuring their access to land and local power in North Kivu, as well as addressing the discrimination they perceive against the Tutsi community. The UN Group of Experts also perceived FDLR positions to be key targets for M23 during their military attacks, stating: “M23 and the Rwanda Defense Force (RDF) specifically targeted localities predominantly inhabited by Hutus in areas known to be strongholds of FDLR and Nyatura groups, …”.

As M23 expanded its territorial control, it continuously replaced local authorities with M23 loyalists and extended its control over all aspects of local governance in the occupied territories. In doing so, it also tries to control the local economy in North Kivu, including mineral supply chains. Originally, it mainly operated checkpoints and taxed minerals smuggled to Rwanda, alongside other trade flows. Map 2 overlays M23’s areal control in early 2024 with North Kivu’s artisanal mining sites mapped by IPIS, revealing that M23 controlled hardly any mining sites after more than two years into the rebellion. Only in late April 2024 did the group move into North Kivu’s mineral-rich areas and start to engage in coltan (tantalum) production. Ever since, it has expanded its area of control into various mineral-rich areas in Masisi and Kalehe territories.

Map 2: M23 influence on mining areas in North Kivu.

The displayed mines constitute a non-exhaustive list of those in eastern DRC, including only those visited by IPIS and its partners

At the regional level, the trade of eastern DRC in general, and minerals in particular, has traditionally been linked to East Africa. Several important trade corridors exist in eastern DRC that direct gold and 3T minerals via Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, and Kenya to the world market. Additionally, large-scale cross-border smuggling has been a significant problem in the region for decades. For a long time, Uganda was the main exporter of (smuggled) Congolese gold, while Rwanda was the main exporter of Congolese 3T minerals. However, Rwanda has also become an increasingly important destination for smuggled gold from DRC since 2017. Consequently, Uganda and Rwanda have competed over the past years, to be the main gateway for Congolese gold to the world market. Gold has become both countries’ most important export product by value, accounting for a roughly estimated 48% of Uganda’s and 31% of Rwanda’s total export value in 2022. For Rwanda, the share of mineral exports altogether also rises above 40% of the total export value, as it also exports considerable volumes of tin and tantalum (which are also partially smuggled into the country from DRC).

The above competition and its impact on conflict financing need to be contextualized. The rivalry over Congolese gold export routes is part of larger regional geopolitics and (economic) regional integration dynamics. Eastern DRC is an important marketplace for its neighbors beyond mining, including for agricultural products, consumer goods and services.The DRC is the second import destination for Rwandan exports, accounting for an estimated 25% of Rwanda’s total export value. These exports include rice, raw sugar, refined petroleum, frozen fish, etc.

Finally, minerals also play a role when explaining governance problems and wider insecurity in eastern DRC. The Congolese government struggles to regulate the mining sector in eastern Congo. Its efforts are further undermined by numerous security problems. The Congolese army has acquired a poor reputation, both with regard to its military strength, as well as its human rights record. Its soldiers have also developed several illegal ways of generating revenues, in- and outside the mining sector. Additionally, more than a hundred armed self-defense groups persist in eastern DRC, and while their original raison d’être has faded at times, they sustain themselves through mining revenues. As insecurity undermines mining governance, various actors continue to profit from the fraudulent trade and smuggling into neighboring countries. Global Witness, for example, accused (presidential adviser and former Rwandan Minister of Defense) James Kabarebe of being involved in the organization of mineral smuggling into Rwanda during the 2010s. Such actors and individuals clearly benefit from the status quo, and the persistence of insecurity in eastern DRC, and thus also from M23’s revival.

Is there a risk for regional escalation?

The risk of a further escalation into a regional conflict continues to rise. Rwanda’s support to M23 and the participation of its soldiers in military offensives in DRC violates the territorial integrity of Congo. Tshisekedi’s strategy to call on additional troops from regional partners has since 2021 provided new boots on the ground against M23 and other armed groups. At the same time, it has further incited regional rivalries.

Ugandan soldiers have been deployed to Ituri and the northern part of North Kivu (Grand Nord) since November 2021, within the framework of “Operation Shujaa” to fight the Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) rebels. Analysts however also referred to other economic, geopolitical, and security motives for Uganda, notably the protection of its oil deposits and infrastructure around Lake Albert, and the construction of roads to expand the market for Ugandan goods.

In 2022, Tshisekedi invited a peacekeeping force from the East African Community (EACRF) but soon became highly critical of the force’s lack of aggressiveness against M23. Kinshasa even leveled accusations of EACRF ‘cohabitation’ with the rebel group. The regional force’s mandate was not renewed after a year, which also inflicted damage to the EAC-led Nairobi Process for peace and security in eastern DRC.

While EACRF had to leave, Tshisekedi allowed the Burundian contingent of EACRF to stay through a bilateral agreement in 2023. M23, on the contrary, firmly denounced the presence and activities of EACRF’s Burundian troops. Burundi, in turn, accused Rwanda of supporting the Burundian RED-Tabara rebels in DRC — something Rwanda denies. Burundian president Ndayishimiye stated last week “Don’t think this is just about Congo. Today, Rwanda is advancing into the DRC. Tomorrow, it will come to Burundi. We know that it is training young Burundian refugees to prepare them for this war.”

After chasing EACRF, Tshisekedi invited a mission from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) into the DRC, authorizing it to have 5,000 troops from Malawi, South Africa, and Tanzania. In the end, only about 1,300 troops have been deployed. Its deployment has been criticized by Rwanda. After 13 SADC troops were killed by M23 end of January, both the presidents of South Africa and Rwanda lashed out at each other.

With all these foreign troops present on Congolese territory — and with the eastern neighbors all operating in their (former) ‘areas of influence’ — the current situation is beginning to look frighteningly similar to that of the second Congolese war…

Further reading