Past October, violence resurged in North Kivu province, as clashes intensified between the Movement of March 23 (M23) and various local militias, as well as the Congolese army (FARDC). An additional 200,000 people have been displaced last month, exacerbating the dire humanitarian situation in the province which already counted over 590,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) due to the M23 crisis prior to the latest upsurge of violence.

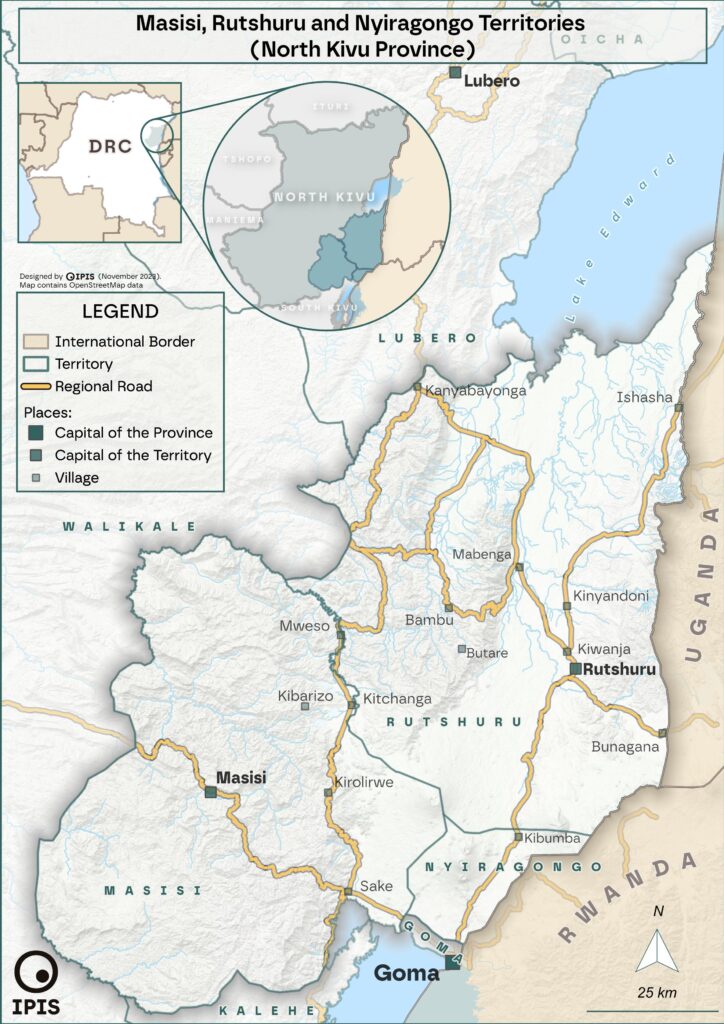

After a six-month lull in fighting, a coalition of local self-defence groups, known as ‘Wazalendo’, launched a series of offensives against M23 along two main frontlines: the Mweso-Kitchanga-Kirolirwe road in Masisi territory, and the roads linking Kiwanja with Mabenga and Ishasha in Rutshuru territory. Over the next weeks, this triggered fierce counter-attacks by M23 against towns it lost earlier, such as Kitchanga, Bambu, Butare, Kibarizo and Kinyandonyi. They reportedly even engaged in the shelling of FARDC positions near Kibumba, only 20km away from the provincial capital of Goma. (See map.)

As fighting continues, chances of de-escalation in the near future look few and far between.

Context behind the current escalations in violence

The ongoing M23 crisis in North Kivu began nearly two years ago, marking the second major iteration of the group’s rebellion against the Congolese government. M23s first offensive began among a group of officers dissatisfied with the poor implementation of a peace treaty signed, on 23 March 2009, between Kinshasa and the rebels of Congrès national pour la défense du peuple (CNDP), which enabled CNDP’s integration into the DRC’s military. Besides proclaiming to enforce the terms of the peace agreement, M23 increasingly claims to defend the interests of Congolese Tutsi and Kinyarwanda-speaking minorities. In M23’s discourse, the grievances of these minorities revolve around threats by Hutu militias and the state’s ineptitude to protect them. Since its ‘resurgence’ in November 2021, the group has captured almost all of Rutshuru territory, pushed into Masisi and secured control over major axes linking the rest of North Kivu to the provincial capital of Goma.

The recent resurgence of violence follows the breakdown of a fragile ceasefire between the M23 rebellion and the FARDC. Announced on March 7, 2023, it was meant to facilitate the withdrawal of M23 from territory it occupied in Masisi and Rutshuru, and to open a space for dialogue with the DRC government. Very little progress has been made however, and both the Congolese government and M23 have continuously accused each other of violating the ceasefire. While Kinshasa gave September 24 as a final deadline for M23 to withdraw, it blamed the rebels of encroaching upon positions (near Kibumba) it had previously handed over to peacekeepers of the East African Community Regional Force (EACRF).

The fighting occurs during the run up to presidential elections in the DRC, planned for the end of December 2023. At the start of his administration in 2019, incumbent president Felix Tshisekedi promised to put an end to violence in the country’s east. Yet measures taken to stabilise North Kivu, such as the declaration of a state of siege in May 2021, have had little success. On the contrary, the M23 rebellion has resurfaced during the same period. Looking to salvage the image of his administration prior to the elections, Tshisekedi seems intent on military advances against M23, rather than diplomatic efforts. He has also ramped up nationalist rhetoric against Rwanda, which is widely accused of backing M23.

Meanwhile, public opinion in North Kivu has grown increasingly critical of the incumbent administration, especially after the army violently cracked down on a protest in Goma against the UN peacekeeping mission (MONUSCO) in August 2023. In response to public indignation, Tshisekedi called for an accelerated withdrawal of MONUSCO, and replaced the military governor of North Kivu with FARDC Major General Peter Cirimwami. The UN Group of Experts reported in 2022 (Annexes 41 and 50) that the latter allegedly supported the ‘Pinga-pact’ between several armed groups in May 2022, and that his forces fought shoulder to shoulder with armed groups against M23. At odds with previous disapproval from Kinshasa, Cirimwami’s appointment seems indicative of Tshisekedi’s desire to gain military victories in the East close to election day.

Map: Simon Schweitzer

Main conflict dynamics and actors

As the latest M23 insurgency enters its third year, the number of parties involved is steadily increasing. This makes conflict resolution all the more difficult, diminishing prospects for peace, both locally and regionally.

M23 continues to bolster its military strength. According to the most recent UN Group of Experts’ report (pp. 14-17), it trains new recruits (their total number of combatants was estimated at around 3,000 in March 2023), tries to establish new alliances (for example with the armed group Twirwaneho in South Kivu), purchases new military equipment, and benefits from military support from the Rwanda Defence Force (RDF).

Aiming to halt M23’s expansion, but restricted by the terms of the ceasefire, the FARDC seems to have chosen to fight the group by proxy. This through covert military and financial support to a coalition of Congolese armed groups, including but not restricted to Alliance des patriotes pour un Congo libre et souverain (APCLS), Nduma Défense du Congo-Rénové (NDC-R), Collectif des Mouvements pour le Changement (CMC), Mouvement Patriotique d’Autodéfense (MPA), and Nyatura groups. Even elements of Kigali’s sworn enemy, the Forces Démocratiques de Libération du Rwanda (FDLR) have joined the coalition. This collaboration was recently consolidated under the watch of military governor Cirimwami, when he met armed groups’ representatives in Mubambiro in September, ostensibly to discuss Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR).

These armed groups have unified under the name ‘Wazalendo’ (meaning ‘patriots’ in Kiswahili) but remain above all a loose—fragmented—agglomeration of local self-defence groups. Besides material and logistical support from the army, the government seems to provide some legitimacy to these ‘patriots’, adopting draft decree n°23/014 of May 22, 2023, which established the Réserve Armée de la Défense. Additionally, some prominent politicians have voiced their careful support, the Minister of Foreign Affairs stating that, “you cannot blame a Congolese for taking up a weapon to defend his country”.

On top of the existing abundance of armed groups in North Kivu, several private military companies (PMCs) have arrived in the province over the last year. The FARDC has contracted Agemira RDC and Congo Protection to maintain the fleet of the Congolese air force, and to provide military training to the army. Congo Protection currently has around 1,000 private soldiers in the DRC. These private contractors have also been assigned to guard three newly purchased combat drones, which were shipped a few weeks ago to the border with Rwanda.

Meanwhile, the international community has deployed several peacekeeping operations in North Kivu. Yet paradoxically, as fighting continues to escalate, the days of the two largest of these seem numbered.

The UN peacekeeping mission is facing the reality that it has overstayed its welcome over the past few years. Despite its size and length, MONUSCO has failed to stabilise eastern DRC, and it is deeply unpopular in North Kivu. The mission has also become an easy scapegoat for Congolese leaders looking to divert criticism away from the shortcomings of the Congolese army (e.g. against M23) and the failing DDR strategy. In the wake of the deadly crackdown in Goma, President Tshisekedi echoed this disillusionment with MONUSCO and announced at the UN General Assembly in September that he wished for the accelerated departure of the force. Despite this, MONUSCO and the FARDC have still launched a joint military operation, ‘Springbok’, to stop M23 from invading Sake or Goma.

The other major peacekeeping force, the East African Community Regional Force (EACRF), arrived in the DRC in April 2022. Since then, Kinshasa has been deeply critical of the force’s lack of aggression against M23, even levelling accusations of EACRF ‘cohabitation’ with the rebel group. The extent of current mistrust is illustrated by a recent attack of Wazalendo on a Ugandan EACRF contingent. Consequently, Kinshasa has asked the regional force to leave the country after the expiration of its mandate in December this year.

The Congolese government did, however, praise the EACRF’s Burundian contingent. Prompting some sources to speculate that the DRC might consider extending the presence of Burundian troops through bilateral agreements.

M23, on the other hand, denounces the activities of the Burundian force, which it accuses of fighting alongside the FARDC and certain Wazalendo groups. Consequently, several incidents have occurred over the past few weeks between M23 and Burundian troops. The Burundian army reported that two of its supply convoys had been refused passage by M23 in Masisi territory. Meanwhile, the rebels have also arrested several dozens of Burundian soldiers, who they accuse of having fought alongside the FARDC.

Kinshasa is also looking for military support from the South African Development Community (SADC) to tackle M23. Meetings to discuss a SADC force are ongoing, as Kinshasa wants boots on the ground as soon as possible. Yet lack of details on their organisation, including funding, have delayed news of a deployment date.

Risks for a further escalation of violence

Looking forward, the continuation of the M23 crisis, violence, and human rights violations entail a variety of long-term security risks. So far, regional and national strategies to mitigate these have failed, instead undermining prospects for sustainable peace.

Indeed, Kinshasa’s choice to adopt a military route to defeat M23 over a diplomatic one, ignores root causes of conflict in North Kivu, particularly those pertaining to intercommunity tensions over access to land and political power. A narrow military strategy will, if successful, merely suppress M23, but will not resolve the local and regional frustrations that have enabled it to thrive.

The past two years of violent conflict have also spurred xenophobia, particularly against Congolese Tutsi and other Kinyarwanda-speakers. This has been instrumentalized by M23 to legitimise its expansion, claiming that it does so to protect the Tutsi community against an alleged genocide.

Furthermore, while the FARDC’s strategy of a proxy war (through collaboration with local self-defence groups) may grant military results in the short-term against M23, it also threatens to embolden the same armed groups behind the current conflict’s longevity. Critically, renewed recruitment and rearmament by these armed groups undermines past and future DDR initiatives. Support to Wazalendo groups will most likely precipitate a cycle of violence which outlives the current crisis.

Finally, Tshisekedi’s decision to shift away from international peacekeeping, towards regional—or even bilateral—security arrangements involves serious risks. A hasty withdrawal of UN troops from the eastern DRC could create a security vacuum, and risks facilitating additional abuses by armed groups against the civilian population. It is unclear whether the Congolese army has the capacity to fill this void. In the meantime, regional security agreements do offer the DRC some new allied boots on the ground. However, when these arrangements involve the deployment of troops from neighbouring countries, it risks inciting regional rivalries, which may also flare on Congolese soil. This threat is real, considering the rising tensions between M23 and the Burundian contingent of the EACRF, and the UN Group of Experts’ reports and denunciations of continuous direct interventions by the RDF on Congolese territory. Meanwhile just last month, the UN Special Envoy to the Great Lakes warned for a potential direct confrontation between the DRC and Rwanda. Ringing the alarm due to the ongoing military build-up by both states, the lack of a constructive dialogue between Kinshasa and Kigali, and the persistence of hate speech.

Picture: M23 combatants marching into Goma in November 2012

Further reading

Related IPIS briefings

All articles and other news items referenced in this briefing come from third party media sources. Not being the author, IPIS is not responsible for the content of the news items or articles contained or referred to in this briefing.

This briefing was produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of the editorial is the sole responsibility of IPIS and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union.