Ce briefing est également disponible en Français.

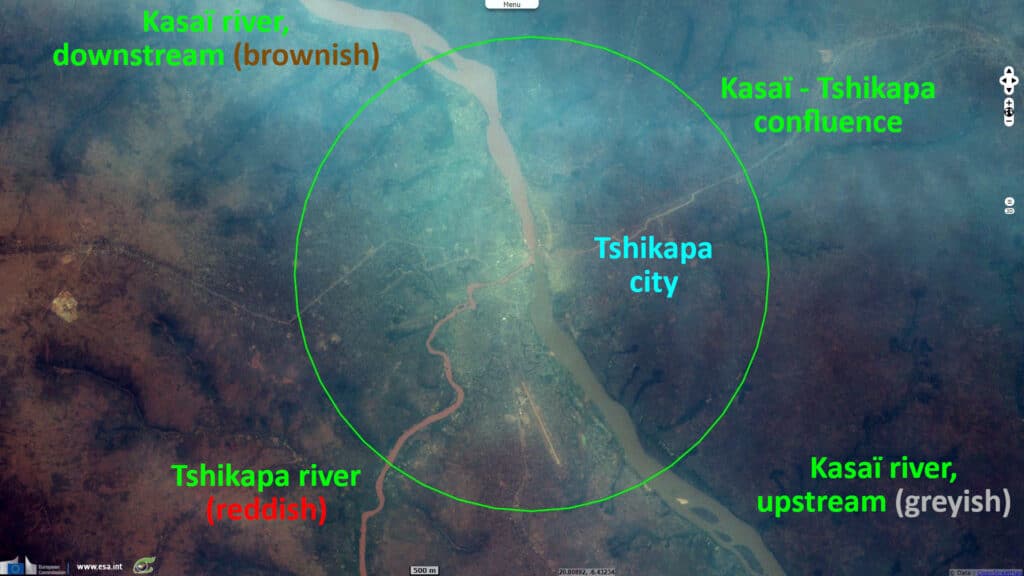

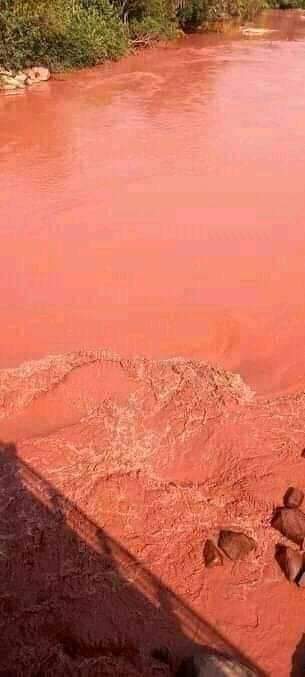

About a year after the news reached the world press, hardly anything has been heard about the environmental disaster allegedly caused by the Angolan Catoca diamond mine. As a reminder, in late July 2021, local media first reported on the brownish-red discoloration of hundreds of kilometers of the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Tshikapa and Kasai rivers due to pollution from ‘industrial diamond mines’ in neighbouring Angola’s Lunda Norte and Sul provinces. Satellite images published a little later traced the origin of this pollution front to a tailings pipe rupture at the Catoca mine in northern Angola. While many facts surrounding the incident to date remain unclear, what has come to light is a glaring lack of leadership on the part of those politically in charge in Congo and Angola to ensure accountability and remedy for the harms caused.

The disaster, according to official Congolese government reports, killed 12 people, sickened thousands of river residents, cut off hundreds of thousands of people from their daily water supply, and caused mass mortality among aquatic life and livestock on the banks. According to a (yet unpublished) recent survey by IPIS’ Congolese NGO partners GAERN and CENADEP, in Kasai province 13 of the 18 health zones were affected by the pollution. These zones include more than 200 villages and almost 1 million inhabitants. The NGO survey also revealed that more than 80 % of the population along the affected rivers consume river water, whereas less than 20 % draw their drinking water from the facilities run by the REGIDESO water company.

The disaster, according to official Congolese government reports, killed 12 people and sickened thousands of river residents.

In addition to these immediate harms, the lack of access to clean drinking water deteriorated the general health and hygiene conditions in the affected areas, leading amongst others to a typhoid outbreak in October last year. Furthermore, the dramatic reduction of fish stocks negatively impacted food security and economic activity in these river-dependent communities, in a way that is likely to be felt for years to come. One year after the event, the dossier is even murkier than the affected river water, and the Congolese and Angolan authorities shroud themselves in silence.

Catoca is the fourth largest diamond mine in the world with an annual production worth USD 800 million. The main shareholders of the Sociedade Mineira de Catoca (SMC) are Angolan state-owned Endiama and Alrosa (41%), the Russian diamond miner that produces the world’s largest volume of diamonds. According to the Financial Times, the Angolan attorney-general would have added 18% of the shares to the Angolan state’s portfolio in the last quarter of 2021, bringing its total package to 59%. The shares belonged to Lev Leviev International, a subsidiary of the China Sonangol group. The Chinese shareholders are now said to be challenging that decision in Angolan courts.

The already scarce communication on the part of corporate stakeholders fell completely silent after September 2021. In that month, SMC announced an expedition to take samples in the affected rivers with the goal of ‘proving with lab data that there are no heavy metals in the river systems’. No test results were ever published of that ‘scientific’ expedition. The same goes for announced environmental audits that also had to ‘reconfirm that there has been no environmental damage’. Summarizing the results of SMC’s ‘investigation’, it says that sand and clay leaked into the water from a leak in a tailings basin. To the layman, this does not seem to be a problem. However, the determination ‘sand and clay’ says nothing about the chemical composition of such particles, only about their size, and is therefore hardly relevant in this case.

Also unpublished are the scientific tests of water quality in the affected Congolese rivers ran by the Congolese authorities. However, during an initial phase of tough, political rhetoric, Congolese Environment Minister Eve Bazaiba announced that preliminary results of tests in the Kasai River showed the presence of heavy metals such as iron and nickel. Further, scientists from the Congo Basin Water Resources Research Center at the University of Kinshasa issued public statements about an ‘unprecedented environmental and human disaster’. They also launched a public appeal with a series of recommendations in August 2021 (see text box below). However, a few months later, a person in charge at the centre reported that due to a lack of funds, it was unable to organise any follow-up on the situation on the ground.

An inhabitant and administrator of Kasai detail the impact of the pollution and what has been done to mitigate the consequences of the disaster. (French)

Call for urgent measures by the Congo Basin Water Resources Research Center of the University of Kinshasa (French acronym: CRREBaC) on August 13, 2021:

- Ensure the immediate cessation of pollutant discharges into the rivers from the source in Angola;

- Establish a plan for hydrodynamic measurements and sampling of water, sediments and aquatic biodiversity upstream and downstream of the CRREBaC station (…) in order to determine the extent of the pollutant load;

- Conduct a targeted field data collection and laboratory analysis campaign as soon as possible, based on the above-mentioned hydrodynamic measurement and sampling plan;

- Assess the socio-economic and environmental impact of the pollution and propose mitigation and remediation measures;

- Strengthen the operational capacity of the CRREBaC monitoring station (…);

- Implement an accelerated training of trainers program to increase the technical and operational capacity of the services involved in water-related disaster risk monitoring;

- Implement a communication strategy to better inform riparian communities for awareness and safety purposes.

The punitive language on the part of the Congolese government, demanding compensation in accordance with the ‘polluter pays’ principle, also quickly died down. Announced government-level consultations with Angola were never heard of again, and an investigation in Catoca at the behest of the Congolese was never allowed by the Angolan authorities. Meanwhile, a government prohibition on the consumption of water from the Kasai and Tshikapa rivers – and their fish stocks – instituted in August 2021 remains in place to this day. The Congolese government also failed to fulfil its promise to construct thirty new water wells for the population.

Announced government-level consultations with Angola were never heard of again, and an investigation in Catoca at the behest of the Congolese was never allowed by the Angolan authorities.

In late March 2022, the omertà brought a Congolese MP to interpellate the ministers of Environment and Foreign Affairs. The MP in question is Guy Mafuta, who was elected in the Tshikapa constituency. The nature of his parliamentary questions (see text box below) shows that Parliament and by extension the Congolese citizens are completely in the dark about every key aspect of the environmental disaster. Until today, however, no ministerial response to any of these crucial questions has been publicly uttered.

Parliamentary questions asked on March 28th, 2022 by MP Guy Mafuta to ministers responsible for the dossier of pollution from Angola of rivers in the Kasai (own translation):

To the Minister of Environment and Sustainable Development:

- On August 09, 2021, an official communiqué from your ministry, following that of August 02 of the same year asked the population to abstain from the waters of the Kasai and Tshikapa rivers following its contamination. Has the situation evolved since there has never been a communiqué to the contrary?

- To date, have you assessed the environmental, human and economic impact suffered by our country?

- Do you have reliable results of the water and sediment analyses? When and under what conditions were these samples taken?

- Have you already identified the victims and evaluated the degree of their afflictions?

- What about the Government’s aid? How far has it been channeled? Which provinces and areas were served? Do you have a report on the distribution of the water, knowing that the pollution affected three provinces of the Republic?

- It was the water that was poisoned. How many water wells did you dig to save the population?

- How will you apply the polluter pays principle?

- Beyond administrative sanctions, why not take the legal route to sanction these companies and compensate the populations?

- Following the lawsuit initiated by the 7,879 complaints of the victims of this pollution, what can be the accompaniment of the Government of the procedure of exequatur?

To the Minister of Foreign Affairs:

- To date, have you contacted the Angolan authorities on this issue?

- What about the mixed commission that was to be set up by our two States?

- To which of our two countries does the diligence belong? Why do we give the impression of being so weak and soft in the face of the Angolans?

- How do you view your diplomatic management of this disaster? Is the work completed? If not, what remains to be done?

Due to the many uncertainties about the health risks posed to the communities living along the Thsikapa and Kasai rivers, the Unit of Toxicology and Environment at the University of Lubumbashi and the Department of Public Health and Primary Care at the Catholic University in Leuven, Belgium, took the initiative to independently test the water quality. The results were presented in a conference in Kinshasa in June 2022. This revealed that the water was contaminated with nickel, uranium and other metals, although the exact cause of the fish mortality, deaths and illnesses among residents could not be determined.

Given the complex river system, the long distances involved and the various (diamond) mining and other economic activities along those waterways, the difficulty of connecting pollutants to a single and specific source only increases over time. Again, culpable negligence of the government harms the rights and interests of the population. Such tests should have been done and published right after the incident, including a comparative analysis between results in the tailing basin, in waterways around the mine in Angola and further downstream in DRC.

In March 2022, a class action suit was filed in the Tshikapa District Court by a team of lawyers coordinated by parliamentarian Guy Mafuta representing nearly 8,000 aggrieved people from the region. Several civil society organisations have taken civil action in the case, which claims compensation for damages suffered as a result of alleged pollution by the Catoca mining company of the Tshikapa and Kasai rivers. No representatives of the Angolan company were to be seen at the first hearing. It also remains to be seen whether a Congolese tribunal can enforce anything against an Angolan company, of which, moreover, the Angolan state is now the main shareholder. Regardless of its recently portrayed commitment to improved diamond governance, transparency and anti-corruption, Angola does not have a convincing track record when it comes to protecting the rights of communities affected by diamond mining. While restrictions on civic space render it difficult for civil society to monitor this sector of strategic national interest, activists regularly manage to document abuses, violence and torture of locals by public and private security forces in Angola’s diamond mining areas. In 2018, Angola moreover did not shy away from human rights violations during the expulsion of Congolese refugees and migrants in the diamond-rich border area where the pollution took place.

In short, the only response the hundreds of thousands of Congolese affected by the Catoca mine pollution have felt to date, is the still prevailing prohibition on consuming water and fish from the Tshikapa and Kasai rivers. The inaction by Congolese authorities and failure to provide clean water supplies and relief measures makes the Kasaian population twice a victim. Meanwhile, the world has forgotten yet another crisis in a remote and impoverished area of Congo. This, however, is not due to the matter being resolved but to the complete absence of efforts to seek a resolution. The Angolan government and the Sociedade Mineira de Catoca are unlikely to assume any responsibility towards the Congolese victims, while the Congolese government is culpably negligent. As a consequence, all hope now rests with civil society, academics and lawyers to keep pushing for accountability, remedy and the prevention of further harms.

Further reading:

All articles and other news items referenced in this briefing come from third party media sources. Not being the author, IPIS is not responsible for the content of the news items or articles contained or referred to in this briefing.