KP Civil Society member organisations between May and August 2020 carried out research projects in their home countries on one of three areas of focus, namely benefits of diamond mining to local communities (CECIDE/AMINES, GAERN, NMJD, CNRG, Green Advocates, CENADEP), violence caused by diamond mining (ZELA, RELUFA) and land rights (MCDF). All participants in these national research projects faced the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic and found creative ways to cope with restrictions in their countries. The summaries of the resulting reports can be found here. (Summaries of the reports of ZELA, Green Advocates and CENADEP will be added soon.)

Read the summaries:

Cameroon: The Kimberley Process traceability scheme in the Eastern Region

RELUFA carried out a fact-finding mission in March 2020 to assess the implementation of internal controls by the KP authorities in the Eastern Region of Cameroon. This region borders the Central African Republic (CAR) and is home to the entirety of the country’s – exclusively artisanal – diamond production, of which the estimated annual capacity is only a few thousand carats. The research topic is all the more relevant as Cameroon is considered by the UN Panel of Experts on the CAR to be the transit hub for the majority of diamonds smuggled from that conflict-ridden country. The smuggled diamonds come from both KP compliant and non-compliant zones, with stones from the latter zones being defined as conflict diamonds by the KP. The total current annual illicit diamond flow from CAR has been estimated by research institute IPIS in 2019 at 170,000 carats.

RELUFA’s preparatory literature review included international reports and the institutional and legal framework of the KP in Cameroon. In the course of the field research, a wide array of stakeholders in diamond sector governance were interviewed. These interviews took the form of focus group discussions with artisanal miners and community members, while individual talks were held with traditional leaders, the departmental and regional delegates of the Mines Ministry, mayors, brokers, and representatives of local NGOs, buying houses and KP focal points.

The research team established that at every point of the traceability chain oversight of the Cameroonian authorities is virtually non-existent and, even worse, that KP focal points systematically facilitate the diamond trade themselves.

Producers and middlemen do not hold licenses (cartes d’artisan, cartes de collecteur) nor the Cameroonian nationality in often cases, though the involvement of non-Cameroonians in these activities is prohibited by law. KP focal points hardly or not at all carry out on-site controls and hence don’t perform their basic duties such as gathering production statistics and checking the provenance of diamonds. Miners have not filled out production registers since 2016, the year of the last KP review visit. Such registers are the first and therefore most vital link of the paper trail that should guarantee the Cameroonian mining origin of exports under the country’s KP system.

Even further down the chain, where under a normally functioning KP regime duly authorized buying houses and their provincial antennas should centralize the internal trade, blatant non-compliance with KP minimum requirements continues. The last official buying house in the East Region closed in 2016 and production is bought outside government scrutiny by investors residing in the far away cities Yaoundé and Douala. These investors may or may not operate under a buying house license and unlicensed middlemen are sent to the East Region to collect parcels on their behalf. All these actors may just as well trade diamonds in a private capacity and work entirely off-books. Illustrative of the dysfunctionality of the Cameroonian KP system is the common practice of KP focal points looking for buyers on behalf of diamond producers, while tending to the paperwork in the process. The latter includes statistically recording the sales they broker as production and providing slips from production registers held in their offices to – falsely or not – attest to the Cameroonian origin of the diamonds.

Guinea-Conakry: Redistribution of diamond mining revenues to local communities

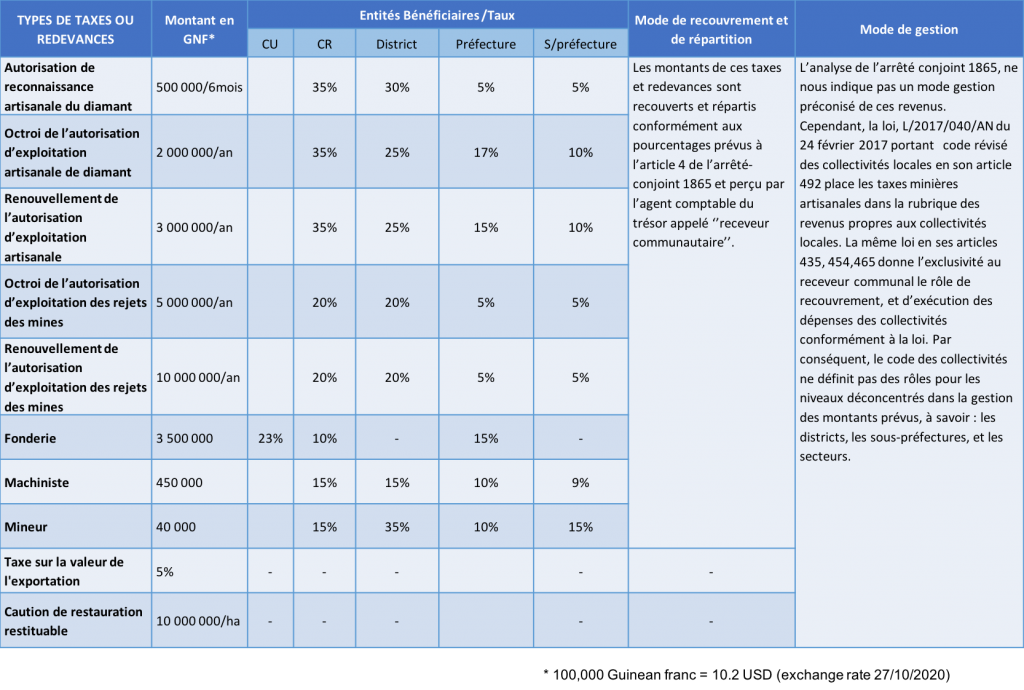

KP CSC members CECIDE and AMINES joined forces in a research project on the redistribution to mining communities of contributions by diamond miners and traders through the tax system of Guinea-Conakry. The research project was carried out in the summer of 2020. The aim of the research was to assess the extent to which diamond sector-related taxes and royalties are returned to the local level, or in other words to verify if and how the Guinean fiscal system generates local developmental benefits. To give a general idea of the size of the Guinean diamond sector: Production, which is entirely artisanal, in 2018 stood at 300,000 carats valuing USD 18 million according to KP figures.

Analysis of the mining code and related regulatory texts shows that Guinean law prescribes a sophisticated redistributional system that aims at compensating mining areas for the disadvantages that come with diamond exploitation. Besides environmental impacts and the reduction of the agricultural labour force, mining also causes a migratory influx of young males, which leads to additional stress and nuisances for local livelihoods, such as alcohol abuse, prostitution and the related transmission of sexually transmittable diseases such as HIV. Positive impacts of diamond mining mentioned by respondents to the study are: supplementary income through financial gains from labour; some infrastructural improvements that facilitate transport such as the refurbishment of bridges; solidarity between miners.

The following table (in French) summarizes the taxes and royalties (‘redevances’) earmarked by law for local developmental purposes (CU is Urban Community; CR is Rural Community):

The research team devised lists of pointed questions about the application of the tax system in practice. Through mobile data collection (using KOBO Collect and Toolbox) and telephone interviews, answers were collected from 63 respondents pertaining to the following categories: 50 % local communities; 30 % umbrella organizations of miners and traders; 20 % local authorities and technical services of the state, including the KP. The team selected two focal areas, which are representative for Guinea’s diamond sector as a whole, namely the prefectures of Macenta and Kérouané.

Rural mining areas are characterized by generalized poverty and the broad consensus among respondents is that the fiscal system does little to nothing to alleviate poverty in their region. More than 80 %, including local authorities, are simply unaware of the existence of the redistributional mechanism in the law. Those who are aware, report that tax collection and fiscal management are surrounded by a lack of transparency, with this problem compounded by secrecy on behalf of producers vis-à-vis local authorities.

Redistribution to local communities however does occur but this is a matter of customary practices. These are steered by local power relationships, and result in patronage and charitable initiatives by investors. The latter are called ‘masters’ and at times show goodwill through gifts and gestures towards social amenities. In this context, some respondents also confirm that small percentages of the value of diamonds are redistributed to customary land owners and the locality. Such practices can have beneficial outcomes but at the same time pose a challenge to the formalization of the sector, while major developmental problems remain unsolved. These include a low level of schooling due to child labour, dangerous working conditions, destruction of forests and arable lands, unavailability of capital to ensure the self-reliance of miners, and a lack of decent social amenities.

DRC: Retrocession of royalties to local communities affected by mining activities in East-Kasai Province

KP CSC member GAERN trained a research team to evaluate the contribution of taxes and royalties due by diamond mining companies (‘redevance minière’) to meet social needs of affected communities. Semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions were held in the summer of 2020 with more than 300 respondents spread over the East-Kasaï Province. This included the diamond capital of the DRC Mbuji Mayi and four territories in its hinterland, where the companies MIBA, SACIM, SML (Société de Minière de Lupatapata) and DIAMEX engage in small and large-scale alluvial mining. East-Kasai is the main diamond producing region of the DRC, one of the most important producing countries in the world in terms of volume (exports in 2019 of 13 million carats valued at USD 160 million – KP figures). Respondents in this research project were representatives of state authorities at the provincial level (Mines Ministry and Mines Administration) and the local level (Services of the decentralized territorial entities), and of the extractive companies concerned.

The latter are criticized locally for occupying hectares of arable land and often causing displacement of local communities. These live in dire poverty with difficult access to health care and drinking water, dilapidated infrastructure, low levels of schooling and low to no access to electricity. Congolese law obliges mining companies to pay royalties based on their sales of minerals, which are to be redistributed to the following levels of government: 50 % to the central government; 25 % to the provincial government; 15 % to local authorities; 10 % to a fund for future generations. The use of royalties earmarked for local development in theory should be negotiated locally with extractive enterprises and be reflected in a detailed description (‘cahier de charges’) of projects concerning social services and infrastructure to the benefit of communities affected by mining.

The research team found that none of the local authorities ever received their part of the royalties, while communities are not aware of the existence of ‘cahiers de charges’ negotiated with mining companies. In practice, the local level is entirely overlooked and management of diamond mining companies only entertain relationships with the provincial and central level of the state. Legal obligations concerning the redistribution of wealth to the local level in other words remain dead letter. Therefore, GAERN will implement an advocacy strategy in the second half of 2020 to sensitize the local population and authorities about the rights of communities to reap fiscal benefits from diamond mining.

Lesotho: Land Rights in Patising Village near Letseng mine

MCDF got involved in 2017 in a land rights case when the community of Patising village in the district of Mokhotlong, Lesotho asked for assistance in their struggle against Gem Diamonds. This is a London-based mining firm that operates the Letseng mine, which is the highest average dollar per carat kimberlite diamond mine in the world. Lesotho reported production of 1.1 million carats in 2019 valuing USD 290 million to the KP.

The Patising case dates back to 2012, when the community was approached by the management of Letseng mine to warn the people of possible impeding danger from the slime dams created by the mine. If these dams burst, there would be no escape for locals, and particularly elderly people in the community. Community members moreover started observing unusual rash and experiencing vomit coupled with diarrhoea upon using water that comes downstream from one of the dams. Letseng Mine at some point even encouraged the community to relocate, but at its own cost.

Initially, the Lesotho Minister of Mining seemed eager to assist the community with strong recommendations and directives to Letseng mine. However, that enthusiasm was short lived for hitherto unexplained reasons. The Minister even started opposing the plea of the community to be relocated. Meanwhile contaminated water suspected to be caused by the slime dams continues to inflict disease on community members and their livestock, with medical reports, according to close relatives of three deceased local inhabitants, indicating that their deaths are related to water contamination. As also the management of the mine adopted an obstinate attitude, MCDF decided to embark on strategic litigation and engaged senior counsel who has brought the relocation claim at the cost of the mine of the nineteen affected households to court. The parties sued are Letseng Diamond mine/Gem Diamonds and the Principal Secretary of the Ministry of Mining.

In the course of its KP CSC project, MCDF in the summer of 2020 prepared an affidavit deposed in July, thus introducing the case to the High Court of Maseru. A second activity under MCDF’s project was to commission a water quality officer of the Department of Geography and Environmental Sciences at the National University of Lesotho to perform an analysis of eight water samples taken in natural streams surrounding Patising village. The resulting report indicated high levels of nitrate and the possibility of high levels of ions, which might indicate pollution by heavy metals. The laboratory however was not sufficiently equipped to reach conclusive evidence and recommended to send the samples for analysis to a fully capacitated laboratory, so that decision-making can be based on full results. MCDF will continue follow-up and will seek funds for additional legal and scientific assistance to the Patising community.

Sierra Leone: Benefits of diamond mining to local communities?

NMJD executed a research project in the summer of 2020 on social and economic benefits of diamond mining to local communities in Sierra Leone, a country which according to KP statistics exported 812,000 carats valuing USD 168 million in 2019. The project targeted two of the country’s three main diamond mining districts, namely Kono and Kenema. Interviews were conducted in four mining communities – Gbense, Tankoro and Nimikoro (Kono) and Lower-Bambara (Kenema). The research team administered five sets of questionnaires to community stakeholders, mining company representatives, members of the community development fund management, chiefs and local politicians. Community representatives were engaged in focus group discussions.

Living conditions in mining areas are reported to be poor and negative consequences communities associate with mining include: gender-based violence; girls dropping out of school and teenage pregnancies; shortage and high prices of basic food commodities; environmental degradation including contamination of water basins and abandoned pits that become breeding grounds for disease-bearing mosquitoes; local land-owners being duped by wealthy foreign mining license owners. In general, communities affected by diamond mining in the areas of research perceive mining as generating few socio-economic benefits. Underpaid jobs for local youth and some scattered infrastructural improvements were cited during focus group discussions as the only tangible benefits to the communities.

Many research questions revolved around the issue of fiscal contributions by companies to local development. Companies are required by law to provide compensation to communities for the adverse impacts of mining. The law and certain policies contain provisions regarding subnational payments by companies that should in commensurate terms translate into development programmes.

Examples of such provisions are the Chiefdom Development Fund (CDF) requiring industrial and artisanal miners to pay an agreed percentage of their annual turnover; a similar arrangement called Diamond Area Commmunity Development Fund (DACDF) targeting artisanal mining operations; surface rents, blasting and crop compensations. Three large scale mining companies that operate in the area of research – Koidu Limited and Meya Mining in Kono, and Sierra Diamonds in Kenema – have signed community development agreements with their host communities as required under the law governing the CDF but the research team found no governmental nor company representatives willing to discuss the implementation of these arrangements.

The perception among communities is that the legal and policy framework is inadequate to address development challenges and that existing laws are not effectively implemented. Corruption in the collection, management and redistribution of mining revenues is cited as the main cause of persisting poverty. Local leaders who receive subnational payments are distrusted and are seen as colluding with large-scale miners to defraud communities. The redistributional mechanism as a whole is considered by local stakeholders as grossly inadequate, badly and selectively implemented, not well institutionalized, poorly accounted for and very much centrally controlled by the government. The system therefore does not provide the space, opportunity and empowerment required for exerting enshrined rights and reaping benefits.

NMJD has decided to fill the gaps of this research project, which were caused by a lack of cooperation on behalf of key governmental and industry stakeholders. Future research will focus on how mining revenues are utilized, how decisions are taken, what accountability mechanisms exist and what needs to be done to maximize community benefits.

Zimbabwe: Alternative livelihoods options for communities in Marange affected by diamond mining

CNRG conducted a baseline survey to establish the current livelihood status and preferred livelihood options of the communities of Marange in Chiadzwa, Mukwada and Chipindirwe wards in Mutare District in Eastern Zimbabwe. Marange is currently ranked as the largest diamond producing deposit on earth. Its diamond fields in 2019 earned the country USD 124 million through the export of 4.2 million carats according to KP statistics. Despite the wealth it generates, Marange seriously lags behind in terms of development. Robert De Pretto, the meanwhile former CEO of Zimbabwe Consolidated Diamond Company (ZCDC), one of the two large scale mining companies currently working in the area, recently witnessed the level of poverty there. During a visit to Chiadzwa in July 2020, he expressed his shock over the fact that the area still had such poor roads and no running water, while children still walked long distances to school, despite sales of billions of dollars worth in diamonds since mining started in 2006. The main reasons for Marange’s underdevelopment are corruption and the destructive nature of extractive operations, which in 2008 also led to the displacement of over 1,000 families to the detriment of the local economy. Since then, the inequality gap has been widening because of non-availability of alternative livelihood options for the local community.

Focus group discussions with 15 local men and 15 women, and key informant interviews – held remotely because of Covid-19 restrictions – were used for data gathering by CNRG in the summer of 2020. Key informants included representatives of community-based organizations, traditional, religious and political leaders, and a women’s rights organization.

Regarding current livelihood activities, the survey found that households mainly engage in home-gardening, livestock raising, bee keeping, brick moulding and subsistence farming. These activities are however not economically interlinked with mining activities in Marange. Moreover, existing livelihoods are inadequate as they contribute little to household incomes: Families indicated that they earn between USD 5 and USD 20 per month through said activities.

The survey further established that young men from Marange resort to sneaking into the diamond fields for artisanal diamond mining. This enables them to earn an income of between USD 200 and USD 500 per month. Artisanal diamond mining is however forbidden by law. It proves to be a risky venture because once artisanal miners are caught, they are subjected to inhumane and degrading treatment which includes having dogs set on them and being beaten by the police and ZCDC security guards. Hundreds have lost their lives over the last decade.

The survey also found that while some locals are interested in securing employment at the mining companies, there is general disgruntlement over their failure and that of government to develop the area. The people of Marange desire to see a thriving local economy spurred by the mining of diamonds. Women are interested in sewing, market gardening or horticulture projects but they need to be capacitated with boreholes, irrigation equipment and sewing machinery. Men and youths are interested in self-help projects like carpentry, wielding and building.

CNRG recommends that a multi-stakeholder conference be convened to discuss alternative livelihood options and to map the way forward for the people of Marange. The multi-stakeholder conference should bring together community leaders, traditional leadership, and diamond mining companies, community-based organisations, civil society organisations, the government of Zimbabwe and prospective investors. CNRG will make efforts to materialize its plans for such a conference over the coming year.

This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of IPIS and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union.

e