The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is an important player in the global diamond industry, with considerable untapped potential. It holds 9% of the world’s known diamond reserves and accounts for 18% of global production of industrial diamonds and 3% of gem-quality diamonds. Despite promising prospects, the country’s diamond sector has been in a prolonged existential crisis, marked by a steady decline in production for more than 15 years.

This report discusses the current state of play in the DRC’s diamond mining sector, including production trends, key challenges, as well as efforts and opportunities to revive the sector and to increase its impact on local development and socio-economic well-being.

Annual diamond output fell from around 30 million carats at the start of the century, to an average of 11.7 million carats per year since 2019. The first significant drop, around 2008, was largely driven by the decline in large-scale production following the difficulties faced by the parastatal diamond miner Société Minière de Bakwanga (MIBA). A second important decrease began around 2017, this time due to falling artisanal production levels.

Industrial mining

Industrial diamond mining in the DRC takes place in the country’s Kasaï region, and over the past decade has been dominated by the large-scale miner Société Anhui-Congo d’Investissement Minier (SACIM), following the collapse of the once-prominent state-owned miner MIBA .

MIBA was once a major economic force in the Kasaï region and a key financier of former President Laurent-Désiré Kabila’s war efforts. Its decline began after losing its most valuable concessions and entering exploitative (or ‘leonine’) contracts with foreign investors – issues compounded by a lack of investment, depleted deposits, and failed (?) contract renegotiations. Allegations of widespread corruption, including large-scale diamond embezzlement, further deepened the crisis. With minimal operational equipment and mounting debt, MIBA’s output fell from 9.5 million carats in 1990 to just tens of thousands in recent years. Although President Tshisekedi, originally from Kasaï, has proposed a revival plan, many view it skeptically due to insufficient funding.

Since 2016, SACIM has become the largest diamond miner in the DRC, exporting 4.32 million carats in 2022. Despite its relatively stable production figures, SACIM’s reputation is controversial as it has been facing diverse accusations, including serious violations of workers’ and human rights, tax fraud, pollution, resource plundering, and failure to contribute to local development. To address accusations of fraud, the government issued a decree in 2022 requiring SACIM to sell its diamonds through five pre-approved Congolese exporters — a move some MPs claimed violated the Mining Code. SACIM responded by cutting its production.

Beyond SACIM and the remnants of MIBA, the DRC hosts numerous semi-industrial diamond mining companies. Their operations are however hardly monitored by government services. Many of these companies reportedly operate under the protection of influential strongmen or members of the national army FARDC (Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo), who often obstruct access to oversight by other government services. This lack of oversight has led to numerous complaints, including environmental damage, declining fish stocks, reduced water supply, and the eviction of artisanal miners from mining sites.

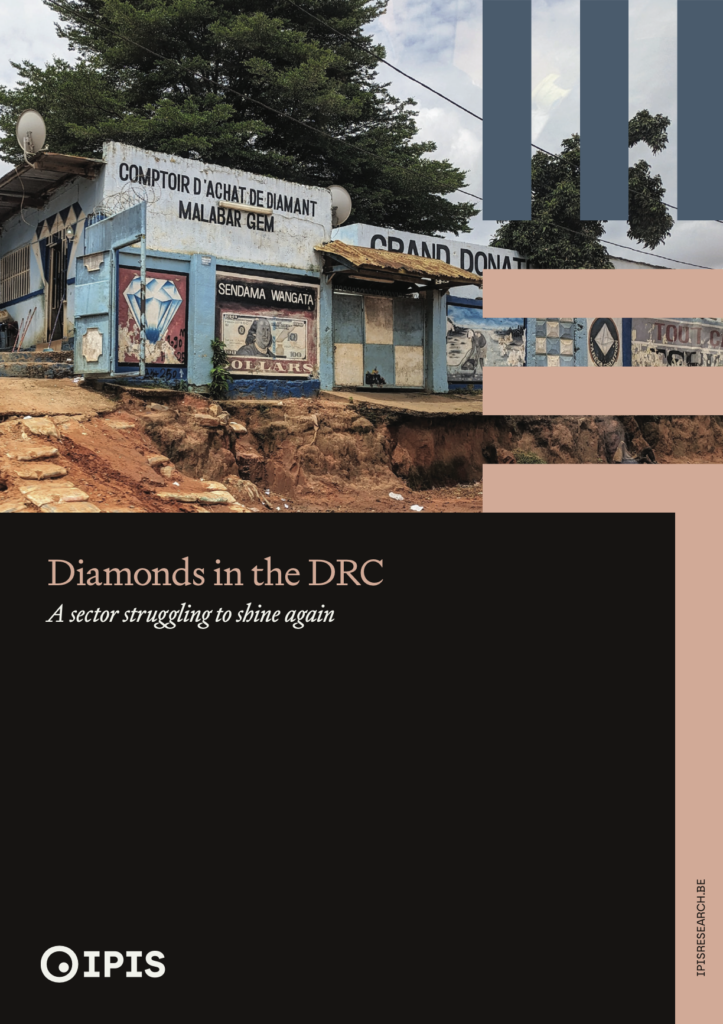

Artisanal diamond supply chain

Since the collapse of MIBA, artisanal miners have become the primary diamond producers in the DRC. A roughly estimated 450,000 artisanal miners provide 60% to 80% of the country’s diamond export volumes. The Congolese artisanal diamond mining sector, however, faces several key challenges, including difficulties for state services to monitor the supply chain, declining production figures, extortion of ASM stakeholders, and insecurity.

The sector is characterized by deep-rooted informality, with many ASM stakeholders evading formal oversight by state agents. Government agencies try to channel the diamond trade as much as possible in the formal supply chain, but are unable to conduct effective site-level monitoring or oversee the complex and countless transactions that characterize the artisanal diamond trade. Consequently, they are obliged to rely on the volumes and origins of diamonds declared by local traders, with no reliable means of verification. The DRC’s internal control system also struggles to effectively address fraud.

The Congolese artisanal diamond sector is likely experiencing its worst crisis since its boom in the 1980s. Over the past decade, production volumes have halved. Decreasing diamond prices, and instability on the world market, allegedly bankrupted many local traders. In turn, this affected access to credit, a critical factor in the sector as traders generally pre-finance ASM operations. This financing is now needed more than ever, as shallow deposits have been depleted, pushing miners to dig deeper, generally without adequate tools or safety equipment, which increases the risk of accidents. Frustration with the lack of access to diamond-rich zones, drives local youth to encroach upon MIBA’s largely idle concessions, despite the threat of violent repression by guards or soldiers.

The Kasaï region, heavily dependent on the diamond industry, has been hit hard by the downturn in the diamond sector, leading to a socio-economic crisis and significant emigration. More than 200,000 people have reportedly left the diamond-producing regions of greater Kasaï, relocating mainly to Kinshasa or Haut-Katanga – a migration that has at times contributed to rising ethnic tensions.

How to reverse the decline?

The DRC’s struggle to revive its diamond sector and address key challenges is hampered by major governance difficulties, despite the existence of an adequate legal framework and relevant institutions. Weak implementation, and the entrenched informality of artisanal mining, continue to undermine effective regulation of the sector. Meanwhile, international oversight mechanisms have yielded unsatisfactory results. The DRC is a signatory to the Kimberley Process (KP), a multilateral trade regime designed to strengthen internal controls in an effort to curb the trade in ‘conflict diamonds’. While the country’s regulatory framework meets the KP’s minimum requirements, major challenges remain in comprehensively monitoring diamond production and trade across the country.

Despite its vast geological potential, the DRC’s diamond sector has struggled over the last two decades. This report identifies the main challenges that currently impede the sector’s revival and its contribution to the well-being of local communities. The willingness of numerous stakeholders in DRC to contribute to this report — openly discussing the challenges facing the sector — demonstrates a steadfast commitment to progress and reform, even in the face of many barriers.

Yet, while recent years have seen numerous initiatives to enhance transparency, respect for human rights, and productivity in the DRC’s so-called ‘conflict minerals’ (tin tantalum, tungsten, and gold) and strategic resources (like copper and cobalt), diamonds have largely remained on the sidelines. Several interviewees expressed frustration that the diamond sector — despite its high socio-economic importance, need for investment, and the presence of the Kimberley Process — remains largely overlooked and underfunded.

Downstream markets and the KP cannot absolve themselves of responsibility when imposing standards. Without dedicated financial and technical support, expecting the DRC to meet all requirements and establish full oversight over its hundreds of diamond mines and countless transactions is both unrealistic and counterproductive.

This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of the document are the sole responsibility of IPIS and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union.