As economies are increasingly looking into alternatives to virgin mining of natural resources to secure their supply of critical raw materials, recycling and the aim of a circular economy are high on the political agenda. A case in point is the recent announcement of an EU Critical Raw Materials Act envisioning, among others, the enhanced recovery of rare earth elements from waste streams. At the same time, the EU considers tightening its restrictions of certain waste exports through a revision of the Waste Shipment Regulation.

While industry stakeholders take issue with the supposedly indiscriminate export restrictions across different waste streams, the need to curb the export of so-called “problematic” waste to non-EU countries, seems to be generally acknowledged. Such export restrictions cater to the objectives of the revision of the Waste Shipment Regulation: a) the shift towards a circular EU economy through the promotion of the reuse and recycling of waste within the EU; b) preventing the export of waste and the related environmental and health-related problems to non-EU countries, also by tackling illegal waste exports.

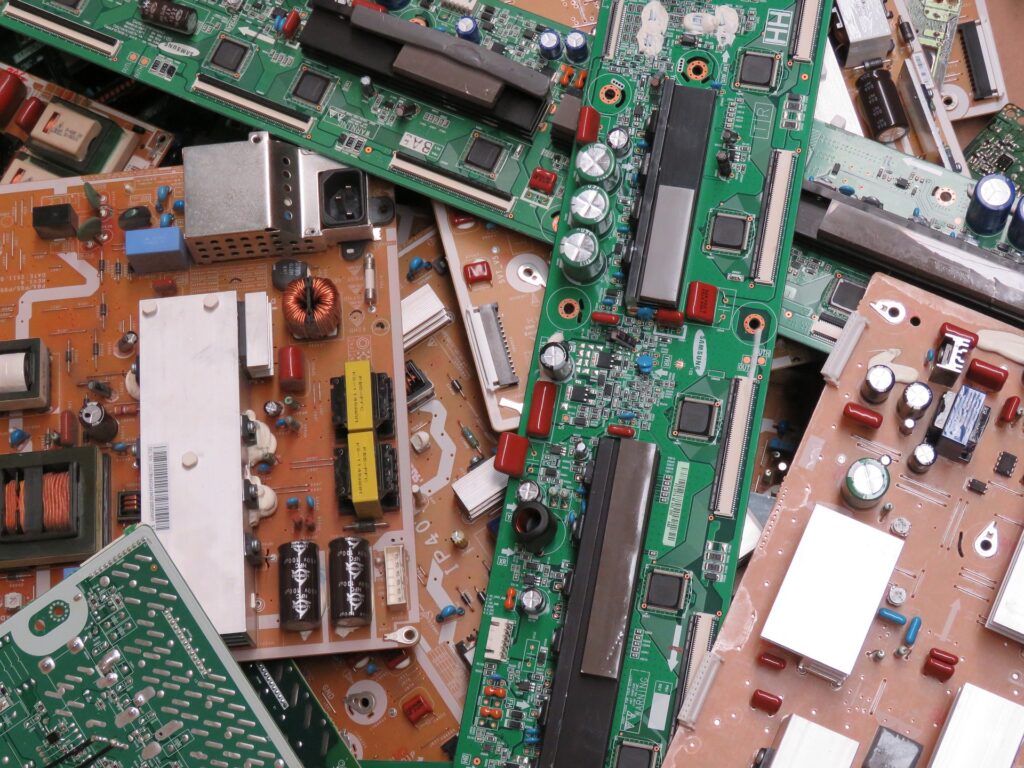

One of these “problematic” waste streams, which is not explicitly addressed by the proposed revision of the European Waste Shipment Regulation, but whose global transboundary movement is already heavily restricted, is unprocessed waste from electrical and electronic equipment (e-waste). Such waste is generated from all devices with circuitry and electric components involving a power or battery supply.

E-waste is considered one of the global waste streams with the fastest yearly growth. A recent study estimates that 53.6 million metric tons of e-waste were generated globally in 2019. Only about 17% of this global e-waste was documented to be processed in a formal and appropriate manner. An estimated 5.1 million metric tons (9,5%) of the global e-waste were shipped across borders, while 35% of this transboundary movement was controlled and 65% was not.

However, it is regularly pointed out that it is impossible to produce accurate estimates of the transboundary movement of e-waste. Apart from the opacity of uncontrolled and illegal shipments, this is due to the ambiguous and unharmonised notions in the regulatory systems – such as the very definition of “e-waste” – and insufficient national reporting under relevant international instruments. Hence, the produced data differs widely and e-waste moved across borders is sometimes presented as making up as far as 90% of the globally generated e-waste.

Southeast Asian, Central and South American as well as North and West African countries are identified as the principal destinations for uncontrolled e-waste shipments, with the African countries often highlighted as the most important import hubs. These exports are said to be driven by the commercial demand of used electrical and electronic equipment in the importing countries as well as their less strict e-waste legislation making them attractive destinations to avoid higher recycling costs in countries with stricter e-waste regulation.

Informal urban mining of e-waste in these countries is facilitated by uncontrolled and illegal e-waste shipments, inadequate e-waste management and deficient processing infrastructures.

Informal urban mining of e-waste in these countries is facilitated by uncontrolled and illegal e-waste shipments, inadequate e-waste management and deficient processing infrastructures. This results in serious environmental and human rights issues affecting those working in the urban mines and their communities. The problems are well documented and among them are the contamination of soils, precarious working conditions with health and safety issues through exposure to the hazardous and toxic materials contained in the e-waste, human exploitation and other labour rights issues. These issues particularly affect vulnerable groups, such as children and migrants working on e-waste dump sites.

The current international control system for the transboundary movement of e-waste is mainly based on the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal. It was adopted in 1989, entered into force in 1992 and is the only global instrument on the transboundary movement of waste. The EU Waste Shipment Regulation implements the Basel Convention.

Since the introduction of the “Ban Amendment”, which entered into force in 2019, the Basel Convention prohibits the transboundary movement of hazardous waste from state parties that are OECD or EU members (plus Liechtenstein) to countries that are not members of either of these organisations. This prohibition covers both hazardous waste destined for final disposal, e.g. into landfills, and hazardous waste lending itself to resource recovery, recycling or reuse.

But the current prohibitions placed on e-waste exports include a number of loopholes. These loopholes hinge upon the definition of what is considered as “hazardous waste”. For the definition of “waste”, the Basel Convention uses the criterion of the actual or intended “disposal”: “waste” are those “substances or objects which are disposed of or are intended to be disposed of or are required to be disposed of by the provisions of national law” (Art. 2(1) Basel Convention).

The current prohibitions placed on e-waste exports include a number of loopholes.

Under Annex IV to the Convention, which lists the covered disposal operations, equipment exported for the purpose of “recycling/reclamation of metals and metal compounds” is always considered “waste”. Yet, the Convention leaves room for potentially hazardous electrical and electronic equipment to be exported as “non-waste”. Such exported equipment does not fall within the scope of the Basel Convention and escapes control and prohibitions. As per current interpretations, this applies to non-functional equipment exported for the purpose of repair and to functional second-hand equipment exported for the purpose of direct reuse. In practice, however, it is pointed out that second-hand equipment might not remain functional for very long and tends to be disposed of quickly after being exported.

Even if the exported equipment is considered “waste” under the Basel Convention, its export is not prohibited if it is not qualified as “hazardous”. This is the case when the material does not contain any of the constituents with certain hazardous characteristics (as defined in Annexes I and III to the Basel Convention). This takes account of the fact that e-waste can contain valuable materials to be recovered, such as gold and copper. Such precious metals are categorised as non-hazardous waste under Annex IX to the Basel Convention.

Some of the loopholes might be closed with new amendments to the Basel Convention adopted at the latest Conference of the Parties in June 2022 (COP15). When these amendments will enter into force in 2025, hazardous and non-hazardous e-waste will have new definitions and both will be listed in the annexes to the Convention. This will extend the “Prior Informed Consent Procedure” to cover not only hazardous but also non-hazardous e-waste. According to this procedure, even if an importing state does not inform the other states parties of an import prohibition concerning a specific waste, they must prohibit its export, unless the importing state expressly consents to it.

COP15 also saw several countries express the wish to work on the definition of “(e-) waste” so as to limit the possibilities to export e-waste outside of the scope of the Convention. One proposition is for the definition of “e-waste” to be based on the functionality rather than on the repairability of the equipment.

Clearer definitions might improve the data on the transboundary movements of e-waste, contribute to the correct categorisation of e-waste and ultimately enhance export controls.

Clearer definitions might improve the data on the transboundary movements of e-waste, contribute to the correct categorisation of e-waste and ultimately enhance export controls. Nevertheless, loopholes might persist, and a major part of the shipped equipment will likely still not be reported, not or falsely declared or not controlled at all. That is why additional (legal) instruments are proposed to complement the current control system to tackle the (effects of) uncontrolled and illegal e-waste flows to non-EU and non-OECD countries.

On the EU level, for instance, a new study proposes to extend the responsibility of the producers of electronic equipment to the entire international value chain. The idea is to move from an “Extended Producer Responsibility”, as contained in the European Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE) Directive, to an “Ultimate Producer Responsibility”. Only the latter would take account of the transboundary movement of e-waste and hold producers financially responsible for the products’ “end-of-life management”, irrespective of where they end up. Accordingly, producers would be responsible for the collection and recycling of the equipment but also for its traceability along the value chain.

Extending the producers’ responsibility until the end of a product’s life cycle across the whole value chain is also in line with the proposed EU Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence and amending Directive. In its recitals 17 and 18, the proposed Directive calls for human rights and environmental due diligence to be conducted “throughout the life-cycle […] and disposal” of a product and for the value chain to cover “the end of life of the product, including […] its recycling, […] or landfilling”.

As long as non-EU and non-OECD countries bear the human and environmental cost of e-waste recycling, a “true” circular economy will not be realised.

Such initiatives are based on the understanding that, as long as non-EU and non-OECD countries bear the human and environmental cost of e-waste recycling, a “true” circular economy will not be realised. Export (and import) restrictions to prevent e-waste from ending up on landfills in those countries are one step in this direction. But, at the same time, it needs to be ensured that the importing countries have adequate e-waste management and processing infrastructure in place. The consideration of the detrimental impact of e-waste on local communities as well as the protection of human rights and the environment must be central in all the relevant (regulatory) initiatives.

Further reading

the value contained in the waste of tomorrow. Urban Mining is an important part of the Circular Economy and provides a degree of independence from natural resources, increasing

supply security.

All articles and other news items referenced in this briefing come from third party media sources. Not being the author, IPIS is not responsible for the content of the news items or articles contained or referred to in this briefing.